By Caitlyn Hayes, The Coastal Society Communications Intern 2016, Eckerd College Undergraduate Student studying Biology and Environmental Studies

Editors’ Note: The mention of certain products does not imply endorsement by TCS members or officers.

Many of you are marine and freshwater enthusiasts in some way, shape or form. Have you ever given thought to your personal care products (lotions, toothpaste, soap, sunscreen, etc.) and how they interact with the systems you love?

You would think that, like with any product you use, they are safe for you or your pets. Normally, our worst experience with these products would be getting them in our eyes, causing irritation. Concern for the impact of personal care products (PCPs), however, goes beyond worries of eye irritation as they enter waterways. PCP presence in waste water could pose problems for aquatic life in coastal ecosystems. Human health is also potentially at risk if these substances get into drinking water supplies or are absorbed into your body’s blood stream. But how would you know based on the labeling and lingo presented on the product? Despite these problems, unclear labels on these personal care products can be a barrier for knowing what to use and what is safe not only for the ocean, but also for you.

You hear all the time about pharmaceuticals being monitored and the public asked to not dispose of them down sinks; to avoid their presence in our drinking water since the filters at waste treatment plants cannot filter them out. Now microbeads in facial washes, toothpaste, and body scrubs are also being banned due to their effects on oceanic life. These microbeads increase the amount of microplastics in the ocean, as they are made of plastic fibers. When the ban was made on the microbeads, the companies had two years to remove them to find substitutes, and the stores to pull them off their shelves so consumers no longer could purchase these items. So what is to say about the effects of other personal care products on the market?

Imagine it is a beautiful day and you decide you want to go to the beach and bring your family. This is your favorite beach because not only is there fun to be had in the warm sand, but you love to snorkel and just a little ways off the beach is a beautiful little reef where you can explore. The moment you arrive you see the sun is intense today, so you will definitely need to apply a lot of sunscreen to avoid burning your skin. You pull out your favorite brand and apply as much to cover every exposed part of your body. Once smoothed out with no white residue left on your skin, you strap on your snorkel and run to the water. The water is beautiful today, and crystal clear, but you notice that there is a strange film on the surface of the water. The film is shiny, at certain angles has a metallic look, and in some cases looks like an oil floating in water. In the back of your mind you wonder, “What could that be?”

If you are me five years ago, you think it is salt and whale pee hanging out on the surface of the water. Have you ever wondered why sunscreen bottles tell you to reapply when you get out of the water? Like any product, it washes off in water. And as you are making your way to the reef to explore, that film is your sunscreen washing off your body. Have you ever thought about what chemicals are in your sunscreen?

You would think that as a product that has constant contact with the ocean and freshwater due to recreational fun, that it would be safe or tested to be safe for marine life. Unfortunately, while sunscreens require much analysis for skin safety on humans, there is little testing on effects to aquatic life. It is estimated that 4,000 to 6,000 tons of sunscreen enters our oceans from washing off our body every year. There are some products that market themselves as eco-friendly and cause no harm to any species that has contact with them. Consumers should be aware though, that “no harm” can be true for any product based on the type of testing that is done, as well as the concentrations used to test. This can greatly skew the results showing the product is nontoxic or not harmful, if reasonable concentrations or test subjects are not chosen carefully.

Autumn Blum, an alumni from Eckerd College, is an active diver and coral reef enthusiast who decided that she wanted to find a better way to create personal care products by removing the harmful chemicals and replacing them with less or non-harmful chemicals. So she created Stream2Sea® the first performance-based sunscreen and bodycare line without using any ingredients known to be harmful. Oxybenzone, a common active ingredient in thousands of sunscreens and lotions, has been shown to be a mutagen, an endocrine disruptor, and a reproductive toxicant for both marine and terrestrial species, and also humans as it is absorbed into the blood stream. It has been found in human breast milk and urine as it lingers in body and blood stream. Not only is this chemical a toxicant to marine species, but you can also look for other active ingredients, such as, benzophenone-2, octinoxate and parabens on the ingredients label. The purpose of these chemicals are for dispersion on the skin, so Autumn replaced those harmful chemicals with non-nano titanium dioxide, non-nano TiO2. This chemical has been shown to not cause harm to other species. When exposed to concentrations higher than what is likely in recreational water supplies, her sunscreen products have resulted in little to no effects on the marine and freshwater fish, and corals that they have tested.

At the moment there is very little research regarding what is toxic and the exact effects the chemicals have on marine species. So there is no standard for what is considered to be safe for marine life. It is up to customers to make the decision to read the label for the active and inactive ingredients already known to cause harm to marine life and to your own bodies. Get rid of the harmful residue coming off your skin as you swim. Look beyond the marketing lingo and read the labels. Think about the ocean, and your own health!

Sources

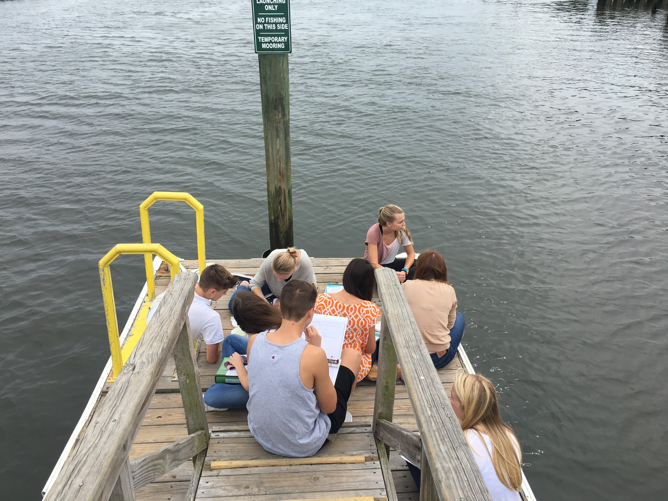

Eckerd College has a small but environmentally conscious student body. The coastal and marine environment proves to be a major draw for Eckerd College students. With over a mile of coastline on our campus alone, students are constantly interacting with the coastal environment. The campus waterfront, situated on Frenchman’s creek near the opening into Tampa Bay, allows students to make regular kayak trips, swimming breaks, and even sailboat rides straight from the school. Service and volunteer work within the community is a high priority for our students, and even part of our graduation requirements.

Eckerd College has a small but environmentally conscious student body. The coastal and marine environment proves to be a major draw for Eckerd College students. With over a mile of coastline on our campus alone, students are constantly interacting with the coastal environment. The campus waterfront, situated on Frenchman’s creek near the opening into Tampa Bay, allows students to make regular kayak trips, swimming breaks, and even sailboat rides straight from the school. Service and volunteer work within the community is a high priority for our students, and even part of our graduation requirements.  The Coastal Society is just one important group on campus that includes a variety of volunteer outreach opportunities. As the first undergraduate program to have a Coastal Society chapter, it provides a great resource and opportunity for students.

The Coastal Society is just one important group on campus that includes a variety of volunteer outreach opportunities. As the first undergraduate program to have a Coastal Society chapter, it provides a great resource and opportunity for students.